In a world of thousands of natural stone varieties being quarried all over the world to the extent there is a massive oversupply of everything there are very few materials that are not only available in big quantities, but also sell easily, because they are widely popular all over the world. The Carrara marbles from Italy, the black granites from India, for example. One could now add the Taj Mahal family of quartzites to this exclusive list.

A decade ago, there was not much quartzite being quarried in the world. Brazil was known its granites. The Taj Mahal family of quartzites, with the quarries located in the state of Ceara (Brazil), was known only to a few people. But look at the numbers today.

While Taj Mahal quartzite current production is estimated to be around 2500 m3 per month, once the other similar materials available in the area are added, the monthly production is roughly estimated to be 10000 to 15000 m3 per month. This works out to be anywhere between 330000 to 500000 sqm per month in the year 2025, an astonishing number by any standard, for what is a natural material. It would be no exaggeration to say that the Taj Mahal family of quartzites have now become the bedrock of the Brazilian granite industry.

Moreover, the popularity is worldwide. Its biggest market is, without doubt, the USA, where according to some estimates about 60 to 80% of the slab production is destined. But the remaining 20 to 40%, which amounts to 50 000 to 100.000 sqm per month, is not a small figure either. Most of this material goes to China or Europe, either as blocks or as slabs.

What explains the huge popularity? According to Mr Paulo Giafarov, well known stone industry expert form Brazil, the reason is its warm, pleasant aesthetics, something that is always popular among specifiers and end consumers. Its versatility allows the architects to combine it with other elements in a home or office, such as furniture. There are different shades, of course, as with any natural material.

There is also another significant criteria: the hardness of Taj Mahal quartzites, which is 7.5 on the Moh scale, compared to the hardness of 3 to 3.5 which is the case with some other materials also considered versatile and with which Taj Mahal quartzite is often compared, namely, Crema Marfil, Bottichino and Travertino. This hardness allows for a larger number of applications, as a premium kitchen countertop material, apart from its use in facades and flooring. The easy availability also means architects can specify it in major projects, something that cannot be said for many other materials.

In industry parlance there are several ways of differentiating the subtle and not so subtle differences between different varieties coming out of the quarry. Same is also true for the Taj Mahal family of quartzites.

The ' Select' version is a homogeneous material with balanced movements.

The 'Standard' version refers to a material with more movements and veins. Sometimes there are white areas on the slabs, or even some fine crystal lines.

The ' Commercial' choice is a material with less 'quality' compared to Select and Standard.

But aesthetics being something totally subjective, the final customer may well decide to classify the varieties in a different manner.

What is the percentage of each of the differentiating varieties coming out from the quarries? This question is hard to answer, since it can vary from quarry to quarry. But one guess would be, perhaps, 10% of the material quarried is classified ' Select', 60% classified as ' Standard ', and around 30% classified as ' Commercial'.

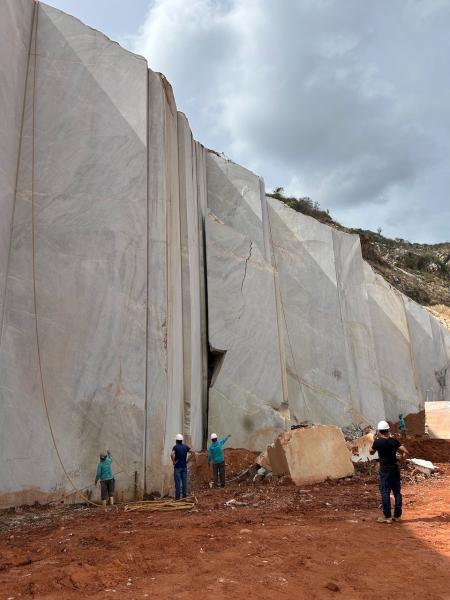

In Uruoca, which is the closest city to the quarry area, there are around 6 to 8 quarries, some are big, like that of Taj Mahal, Perla Venata and Matira and there are also small ones.

How long will the popularity last? Who knows, this is the world of fast changing fashion, but even in such a fickle world, everything suggests that the Taj Mahal family of quartzites will be one of the most popular materials in natural stone for the foreseeable future.

Pictures: Paulo F. Giafarov